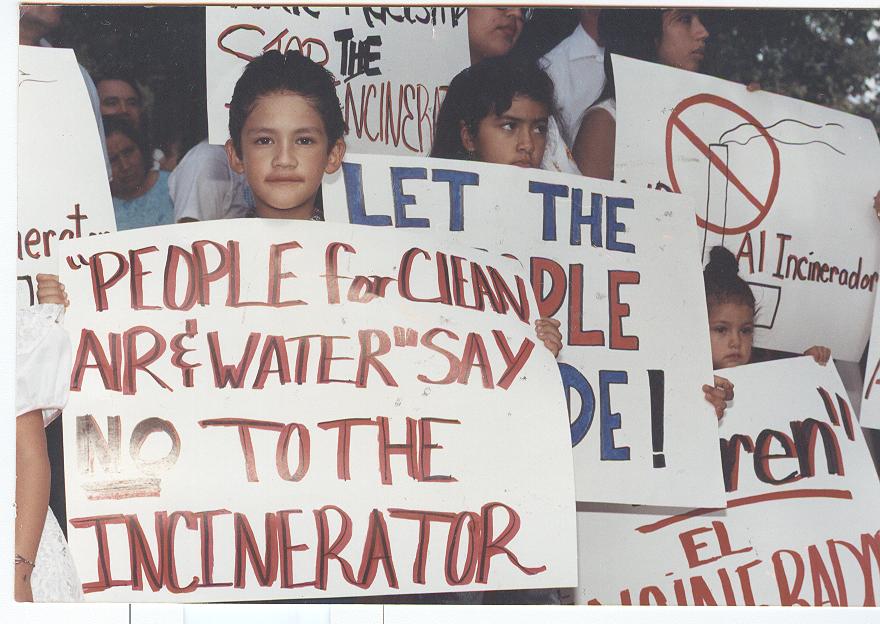

In the mid-1970s, a hazardous waste dump was opened a few miles west of of Kettleman City, a small town that is more than 95% Latino. Most of the residents are farm workers and their families, and many only speak Spanish. Residents learned about the dump in the 1980s and began to protest its location as El Pueblo para El Aire y Agua Limpio, aided by organizations like Greenpeace. In 1988 and 1989, residents successfully opposed the addition of an incinerator to the dump because information was only distributed in English and the owners had not done enough research on the potential health effects of the incinerator for local residents. This struggle is considered one of the birthplaces of environmental justice activism in California.

In 2009, Greenaction observed a cluster of birth defects potentially caused by the dump. Residents supported this claim. However, the California Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Public Health were not able to prove this correlation. The owners of the dump also do not admit responsibility for the birth defects.

In 2013, the dump was granted permission to expand their operations. Residents continue to oppose its operation. The dump's impacts are compounded by the extensive use of pesticides on farms in the areas around Kettleman City.

Today, the Kettleman Hills waste facility continues to operate, despite repeated fines for mishandling of waste. In the future, extreme weather caused by climate change will make it more and more challenging to safely operate the dump. For example, flooding can move toxic chemicals into neighborhoods or the water supply and drought can make it more likely that toxic dust will travel from the dump to town.

Kettleman City also faces other challenges. The town is economically dependent on agriculture, but water-intensive agriculture may not be possible in the San Joaquin Valley as climate change continues to worsen. Droughts, extreme heat, and extreme flooding are increasingly frequent as a result of climate change.

Kettleman City is often considered the birthplace of the Californian environmental justice movement. The StoryMap linked below and the video "Opposing a Toxic Waste Incinerator" cover this history in an accessible way (used in Lesson 2 of the 11th grade CCEJP unit). See book chapters "Kettleman City: Case Study of Community Activism in Changing Times" and "Denormalizing Embodied Toxicity" for more in-depth historical accounts.

It is also a good example of community resilience and resistance against powerful forces. Generations of families (especially the Torres family) in Kettleman City have been active in the fight against environmental injustice. Voices from the Valley includes excellent interviews with community members that highlight this resilience.

The "Opposing a Toxic Waste Incinerator" also provides numerous excellent examples of data divergence. For example, see the competing claims of the Waste Management staff that the landfill was placed in Kettleman City as a result of hydrogeological and geographic features, vs. Luke Cole's claim that it was sited in Kettleman because of racism. See how data divergence is taught in Lesson 3 of the 11th grade CCEJP curriculum and Lesson 2 of the 12th grade curriculum. Either way, this can prompt discussions about intent vs. impact: even if the incinerator was placed in Kettleman for geographic reasons, it means that the negative impacts are borne entirely by Latino families. Is this fair? How can we decide whether impact or intent is more important?

Kettleman City is located along I-5 in the Central Valley, roughly halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco.

One of two hazardous waste dumps in California is located few miles west of the town.

A group of community members, including children, formed El Pueblo Para el Aire y Agua Limpio to protest the addition of an incinerator to the waste dump.

Kettleman City has one K-8 elementary school and no grocery stores.

The community center in Kettleman City was funded in part by the Waste Management hazardous waste dump located outside of town.