How do differently positioned people engage, collectively and otherwise, in imagining and enacting knowledge infrastructures for health equity?

What cultural logics and histories shape the making and application of knowledge about health equity in advocacy, research and policymaking in Louisiana?

How can ethnographic data collection contribute to knowledge production for health equity in Louisiana?

Wednesday, November 3rd 2021, John J. Hainkel, Jr. Briefing Room

A little bit after 9:00 AM

Politicians, physicians and public health advocates debate the accuracy and meaning of data on health care outcomes.

Luneau: “I agree with that—but there was at least some level—just to put it real plainly, the PAs and NPs came in and said: everything’s been great, we’ve had no problems, we’re not working under these doctor’s agreements, we’ve been exempt from that, and everything was great. And a lot of doctors disagreed with that. … This task force is going to flesh out what that information was and how accurate that is. It might be 10 percent of the people it might be 20 percent – I don’t know.” … but that was the purpose of this—not to suggest that we go one way or the other. Just to get the information … “so when it gets back to the legislature we can realistically respond to it”

Giglia (relenting somewhat): but when we have asked to the data, people have said they don’t have it

Luneau: “With all due respect, I’m trying to avoid what’s happening here right now” [voice very stern, clearly losing patience] “This is what happens in the legislature when we have this, and this is what I’m trying to avoid”

Representative from Med Board of Examiners is laughing with hand over is face (middle aged man with a bowtie and suit, glasses, cane)

https://senate.la.gov/s_video/videoarchive.asp?v=senate/2021/11/110321TFHCO

The logics producing inequities are central to legal and scientific structures of power where a focus on progress, objectivity, and efficiency reproduces health disparities, environmental injustice and racial capitalism.

What are some ways of thinking creatively about health equity?

Van Gogh painted “Garden of the Hospital in Arles” while staying there as a patient. The hospital was a charitable institution located in Arles (Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur). Van Gogh was hospitalized there twice and diagnosed by the hospital with “acute mania with generalised delirium”. The former hospital is now a center for van Gogh’s works.

This piece was created by Véronique Vanblaere from Birmingham, Alabama for the Visualize Healthy Equity community art project managed by the National Academy of Medicine.

Vanblaere’s descriptive caption is as follows:

“We need more green spaces in our community. Spaces where people feel safe to walk, run, breathe the outside air during their lunch hour, before or after work, or to replace the cigarette pause. When we put our body in motion, it expands our mind.”

The stated mission of the Visualize Health Equity project is to get more people thinking and talking about health equity and the social determinants of health. The secondary aim of the project is also to take a creative approach to better understand how people across the United States conceptualize the health challenges and opportunities in their communities. The project was managed by the National Academy of Medicine and funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

2017. Vanblaere, Véronique. “Mind Travel.” Visualize Health Equity. National Academy of Medicine. https://nam.edu/visualizehealthequity/#/artwork/40.

Image reproduced here with permission of the artist.

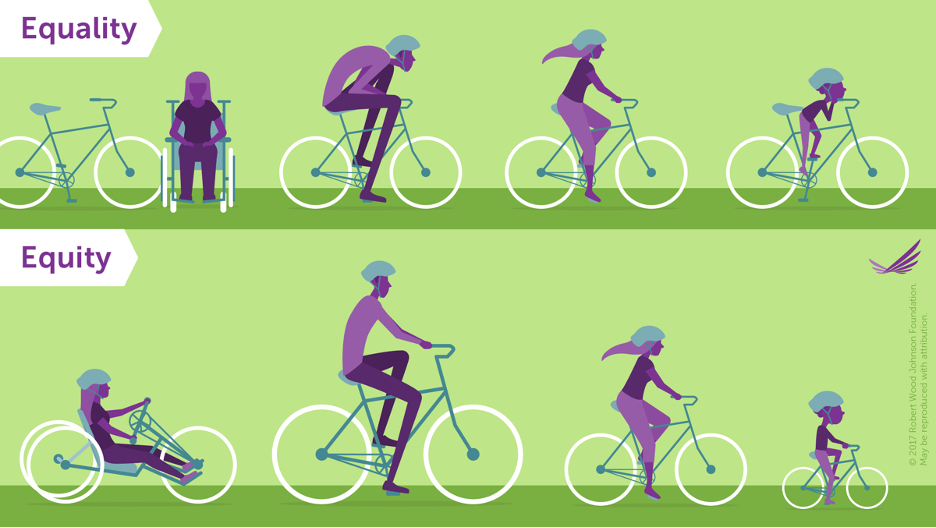

This is a graphic the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation developed to promote health equity. The image emphasizes that equity entails providing the resources that match individual needs, rather than allocating the same quantity or type of resources for everyone. In this framing, understanding difference (on an individual or group level) is integral to equity.

Part of the reason this image caught my attention is because much of the language defining health equity has developed through the disability rights movements, and an emphasis on individual rights.. This framing has provoked critique from anthropological disability studies which argue that “disability is not a category of difference unto itself … rather disability is profoundly relational and radically contingent, (inter)dependent on specific social and material conditions that too often exclude full participation in society” (5).

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2017. “Equity Bicycle Graphic.” Visualizing Health Equity: One Size Does Not Fit All Infographic. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/infographics/visualizing-health-equity.html#/download.

Ginsburg, Faye, and Rayna Rapp. 2020. “Disability/Anthropology: Rethinking the Parameters of the Human: An Introduction to Supplement 21.” Current Anthropology 61 (S21): S4–15. https://doi.org/10.1086/705503.

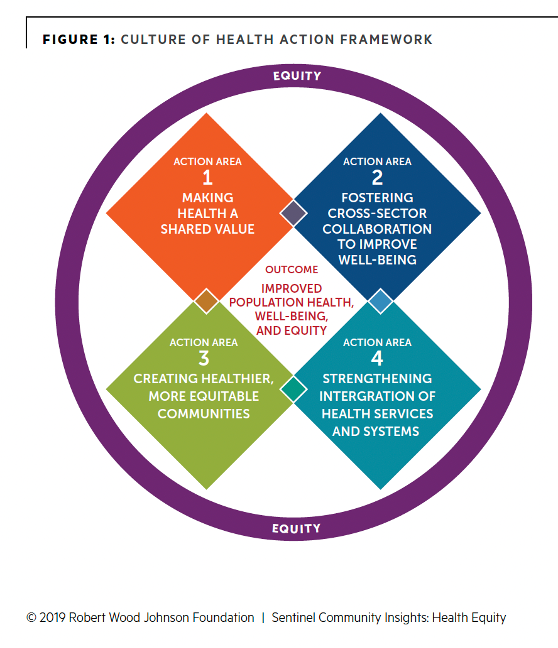

This visual represents the model on which the Louisiana Department of Health’s health assessment initiative developed out of. This framework was developed by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for its Sentinel Communities Surveillance project, which began in 2016 and monitors the development of a “Culture of Health” at 30 different sites across the United States. In this framework, health equity is the foundation of a “Culture of Health”. Specifically, the image is taken from a report RWJF produced that: “provides insight into how 11 communities conceptualize health equity” and how those conceptualizes influence their strategies and approaches for promoting health equity. I wonder here if their overuse of the word equity starts to make it redundant? Overly abstract? RWJF defines health equity as follows: ”Health equity means that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible. This requires removing obstacles to health such as poverty, discrimination, and their consequences, including powerlessness and lack of access to good jobs with fair pay, quality education and housing, safe environments, and health care.” (Braveman et. al, 2017).

Copyright 2015. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation/From Vision to Action: A Framework and Measures to Mobilize a Culture of Health.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine - “Strategic Plan”. This image is on the “About Us” section of the National Academies website. The header for the image is “Our Strategic Plan,” which the text field below the image describes as a plan “to build a more proactive, innovative, and efficient approach” to their work. On the same page, the institution is described as providing “independent, objective advice to inform policy with evidence, spark progress and innovation, and confront challenging issues for the benefit of society”.

2021. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. “About Us”. https://www.nationalacademies.org/about.

These paintings were created by Noshaba Bakht from Kansas City, Missouri for the Visualize Healthy Equity community art project managed by the National Academy of Medicine.

According to Bakht’s descriptive caption for the paintings, she sought to contrast two environments: the trees outside the Art Institute of Houston (US) and the food market at night in downtown Lahore (Pakistan). Bakht notes that the land surrounding the Art Institute has no housing. The night market is “rich in fast food” but there are no “trees to clean the air”.

The stated mission of the Visualize Health Equity project is to get more people thinking and talking about health equity and the social determinants of health. The secondary aim of the project is also to take a creative approach to better understand how people across the United States conceptualize the health challenges and opportunities in their communities. The project was managed by the National Academy of Medicine and funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Image reproduced here with permission of the artist.

2017. Noshaba, Bakht. “Window, Downtown, Houston.” Visual Health Equity. National Academy of Medicine. https://nam.edu/visualizehealthequity/#/artwork/116.

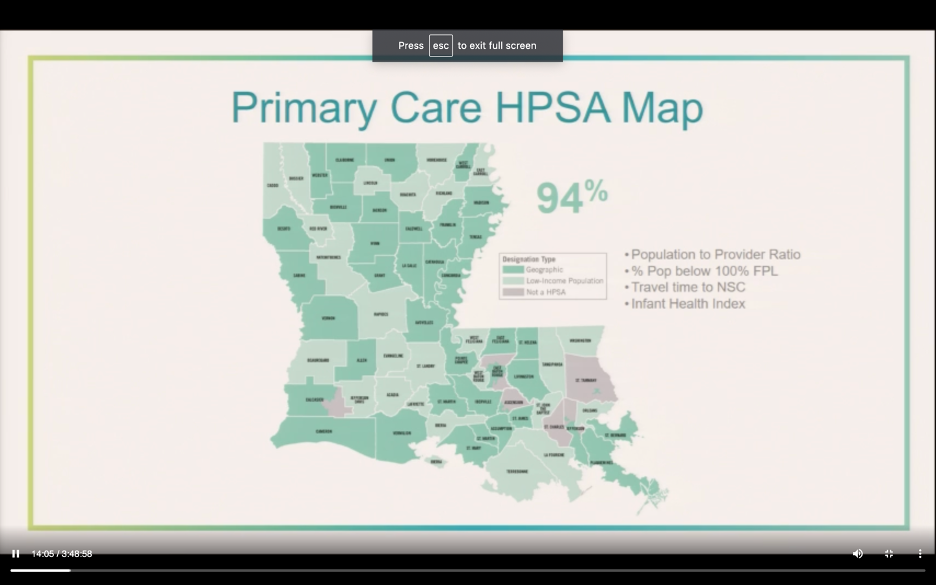

This map was used in a powerpoint presentation given by the Louisiana Department of Health to the Task Force on Health Care Outcomes in the John J. Hainkel, Jr. Briefing Room in Baton Rouge, LA on Wednesday, November 3rd 2021 (the 3-hour meeting was recorded and archived in the Louisiana State Legislative website: https://legis.la.gov/legis/Broadcast.aspx). The primary focus of the meeting was to review data related to how physician assistants (PAs) had performed under the emergency conditions of Covid-19, for which normal regulations on the scope of their practice had been loosened (e.g. they were permitted to do more without physician oversight). The meeting began with this overview of healthcare shortages in the state, as a way to establish the potential positive impact of expanding scope of practice for PAs.

Martin, Melissa and Nicole Coarsey. “Covid-19 in Louisiana - Health Outcomes in Louisiana - Healthcare Professional Shortages in Louisiana”. Louisiana State Legislature Broadcast Archives. 3 November 2021. https://senate.la.gov/s_video/videoarchive.asp?v=senate/2021/11/110321TFHCO.

This is a newspaper article published by the Louisiana Illuminator that highlights activists’ calls for the creation of an office dedicated to improving women’s health outcomes within the Louisiana Health Department. A bill meant to establish this office stalled last summer (2021), prompting Alma Stewart (founder and president of the Louisiana Center for Health Equity) to demand answers for why the bill (House Bill 193) wasn’t passed. It had pass unanimously in the House of Representatives but was held up in the Senate Finance Committee because it was never taken up by the committee chair, Senator Mack “Bodi” White (R-Baton Rouge). White could not be reached for comment by either the Illuminator or Stewart. The specific image heading the article is a photograph of a press conference in front of the Louisiana State Capitol Building held by the Select Committee for Women and Children. Senator Regina Barrow, who is standing at the podium, is the chairwoman of the committee.

Controlled Infertility and Childbirth (Guilbeau Center for Public History). This image is part of a digital exhibit, “Resistance through Persistence: Enslaved Women and Culture in Louisiana.” The exhibit was curated by UL Lafayette History students studying the public history of slavery. The exhibit emphasizes the many ways enslaved women engaged in everyday acts of resistance.

The exhibit is housed in the Guilbeau Center for Public History in the Department of History, Geography and Philosophy at the University of Louisiana, Lafayette. The center is aimed at “helping public historians incorporate diversity, inclusion, equity and accessibility in their work and we focus on projects that decolonize public history … as historians, we rely on rigorous historical research to demonstrate the distinctions between public memory, falsified historical narratives, and evidence based historical facts” (https://www.guilbeaucenter.com/about).

The Guilbeau Center also houses the Recent Louisiana Disasters Oral History Project, as well as other materials from other projects—historians for the center are currently working on building a collection of stories from the UL Lafayette community on the covid-19 pandemic and Movement for Black Lives, which they have named Shared Histories. They are building an archive of photos, typed entries, audio recordings, and videos. They also already have an exhibit at the Arsenal-Cabildo at Louisiana State Museum in New Orleans called “Do No Harm: The Healing Touch of Louisiana Women in Medicine”.

Lastly, the center also has a student-driven Public History project called “Museum on the Move”. This exhibit is designed and curated by students within the interior of the van, which can take exhibits around the state. Travelling exhibits have included: “Cross the Line: Louisiana Women in a Century of Change,”, “Drill Baby Drill” on the oil industry in Louisiana, and “Unmasking Traditions: Mardi Gras in Louisiana,” as well as an exhibit on Hurricane Harvey oral histories.

Abshire, Cody, et al. 2019. “Resistance through Persistence: Enslaved Women and Culture in Louisiana.” UL Department of History, Geography and Philosophy and the Guilbeau Center for Public History. https://www.guilbeaucenter.com/new-page-42.

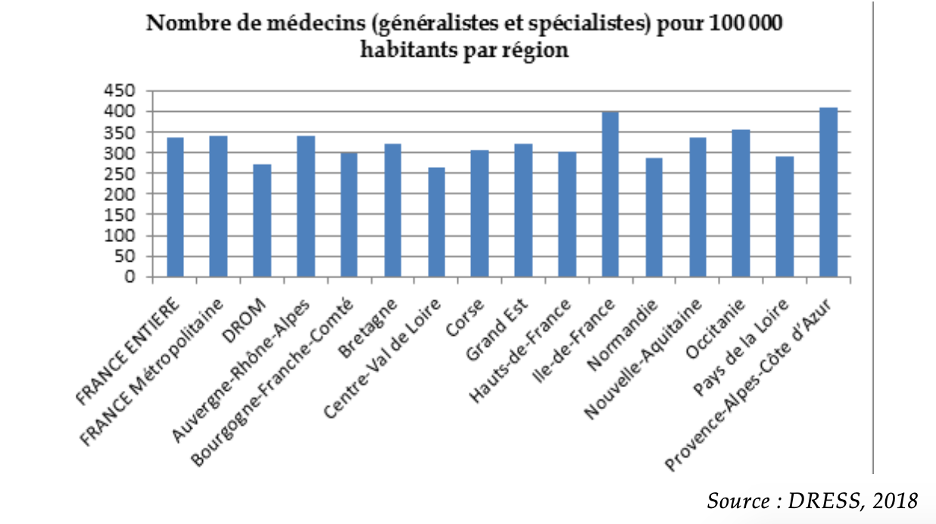

Nombre de médecins (généralistes et spécialistes) pour 100 000 habitants par région. [Physicians (general and speciality) for every 100,000 residents by region].

This chart was published in a Senate report written for the Committee on Regional Planning and Sustainable Development [la commission de l'aménagement du territoire et du développement durable], for a working group on medical deserts [le groupe de travail sur les déserts médicaux] in January 2020.

The chart illustrates the variation in practicing physicians by region in France, with fewer physicians practicing in rural areas like Centre-Val de Loire, Normandie, and Hauts-de-France, particularly relative to more urban areas like Ile-de-France (Paris) and Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur. Other regions with notably disparate access to physicians are the DROM (overseas departments, regions and collectivities).

The report begins with a quote from Georges Clémenceau (French physician, journalist and politician): “Il faut savoir ce que l’on veut. Quand on le sait, il faut avoir le courage de le dire ; quand on le dit, il faut avoir le courage de le faire” [One must know what one wants. Once one knows, one must have the courage to say it; once one says it, one must have the courage to do it].

“Rapport D’Information.” 2020. https://www.senat.fr/rap/r19-282/r19-2821.pdf.

This image comes from the website of newly graduated physician Martial Jardel, who embarked on a project in 2020 to travel through France and briefly “replace” overburdened physicians working in medical deserts. The stated mission of his project is to soigner (heal), recontrer (meet), and apprende (learn). More specifically, the project’s aims are to understand the motivations of doctors who persist in working in areas that are steadily “abandoned” by healthcare professionals, as well as the diverse ways in which medicine is practiced in France--and ultimately to encourage young physicians to consider settling in rural areas. His project received significant media coverage, not just in France but the US.

Jardel, Martial. “Tour de France des replacement.” https://www.letourdefrancedesremplacements.com/.

Margaux Fisher. 30 November 2021, "Following Health Equity Knowledge", Disaster STS Network, Platform for Experimental Collaborative Ethnography, last modified 19 January 2024, accessed 28 November 2024. http://465538.bc062.asia/content/following-health-equity-knowledge