Narration by Kim Fortun

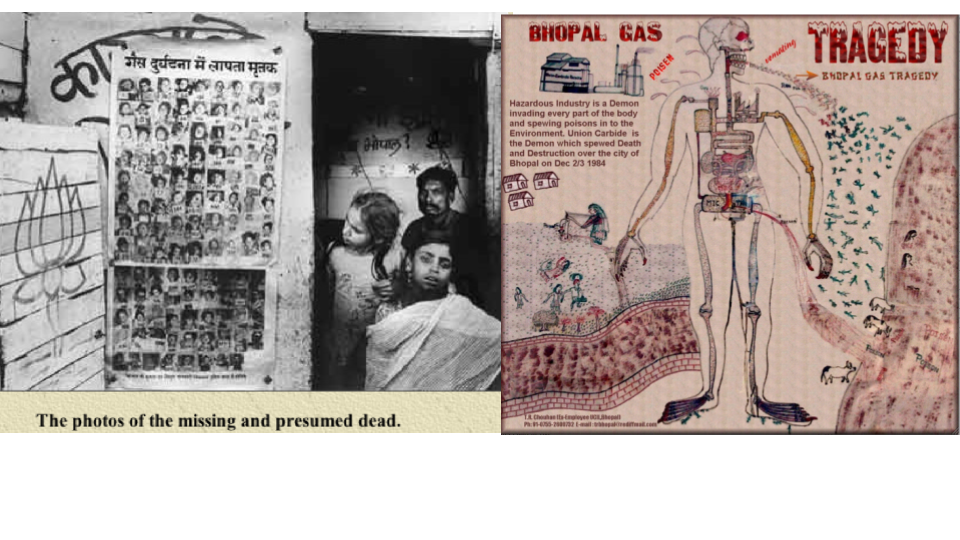

"I started my research -- long ago -- at the site of the 1984 Union Carbide chemical plant disaster in Bhopal, India, which killed thousands in the immediate aftermath and left continuing, deadly pollution in the community’s water supply. Since my research in India in the early 1990s, when the Bhopal case was being heard by Indian courts, I have followed similar hazards in the United States, in the state of West Virginia, where the sister plant of Union Carbide’s Bhopal plant was located, near where I grew up around Houston Texas, and in the River Parishes of southern Louisiana -- a region environmental activists have called Cancer Alley, and, more recently -- Death Alley.

In the early 1990s, as globalization intensified, there was momentum to connect communities around the United States and the world dealing with similar hazards so that they could share knowledge and work together for environmental protection"

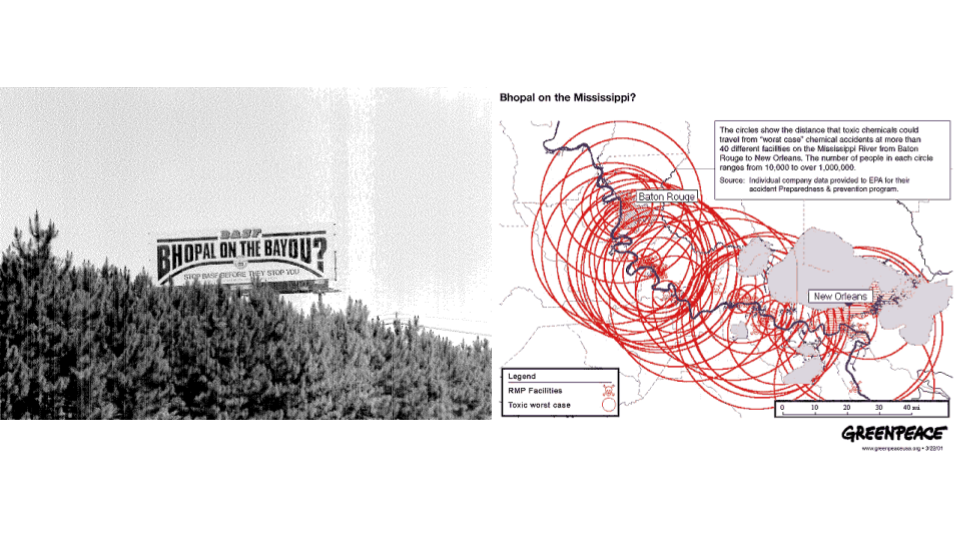

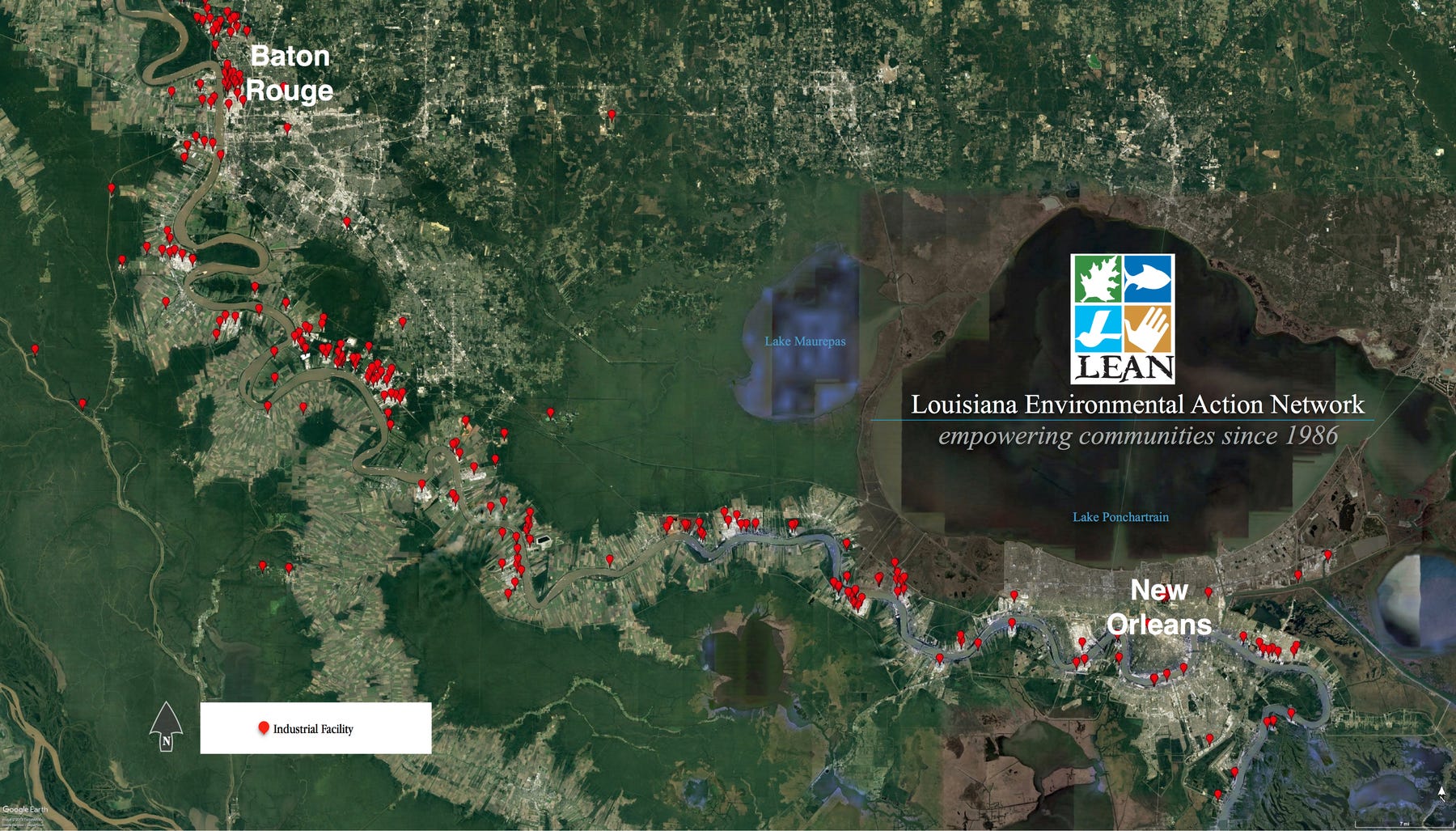

"One result of that activism was this sign on Highway 10 headed toward the River Parishes, warning of the potential for “Bhopal on the Bayou.” Concern about this has motivated my research and teaching throughout my career. It is why I teach the class titled “Environmental Injustice” at University of California, Irvine and why I am part of the collaboration behind this tour. As we’ll share, there is a renewed need today to connect polluted communities around the world because of a surge of plans to to build additional plants in already polluted communities. Communities in Southern Louisiana (and elsewhere) are fighting back."

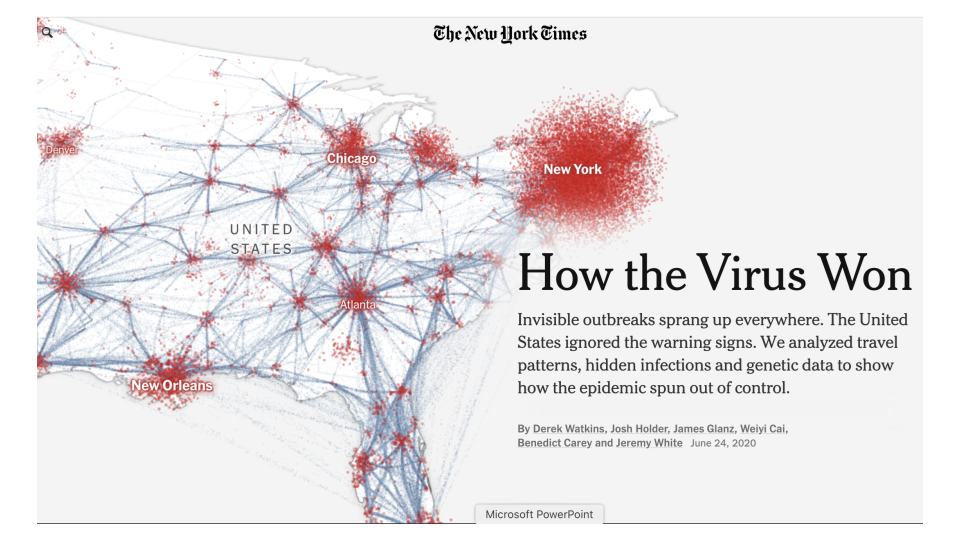

"In April 2020, this region was in the news because it had the highest COVID mortality rate in the country (68.7 per 100,000 people, Laughland and Zanolli 2020). The region was in the news even before COVID-19, however, for having the highest cancer rates in the country, likely due to toxic industrial emissions from the over 150 nearby petrochemical facilities (James et al 2012). Many of the chemical plants are on the grounds of former sugar plantations. Many descendents of people enslaved on the plantations still live nearby; the population is 32 % African American (Kasakove 2020). The health and wealth indicators in the region are soberingly poor. Projections for the future are also sobering…, with predictions of rising heat, increased coastal flooding and extreme weather events.

What connects these data points? This is our focus in this tour.

The Cancer Alley case powerfully illustrates historically produced disadvantage and vulnerability. It also provides powerful examples of Black resistance and resourcefulness."

"The Cancer Alley case exposes many forms of racism -- institutional, structural, interpersonal and systemic -- and many forms of injustice -- health, reproductive, economic, procedural, media and others -- all combining to produce staggering environmental injustice and what scholars and activists have called a “sacrifice zone.”

The Cancer Alley case also points to underlying knowledge problems: to the ways it is often difficult to characterize and act on the problems people face because of inadequate data, methods, analytics tools and research. This produces what we term “data divergence” -- different ways of seeing things, with some people recognizing problems and others discounting them. Often, what people see -- and don’t see -- is shaped by economic interests and deeply rooted, often unspoken racism and sexism."

"Community members, working with activists and researchers, are pushing back -- protesting plans to bring new chemical plants to the area, for example. One recent success has been a stay on further development of a new Formosa Plastics plant because activists were able to demonstrate that graves found on the plant grounds are likely those of people enslaved on the plantation once located there. Markers of death and dispossession are thus becoming more visible and actionable. There are openings for change and we need to move through them.'

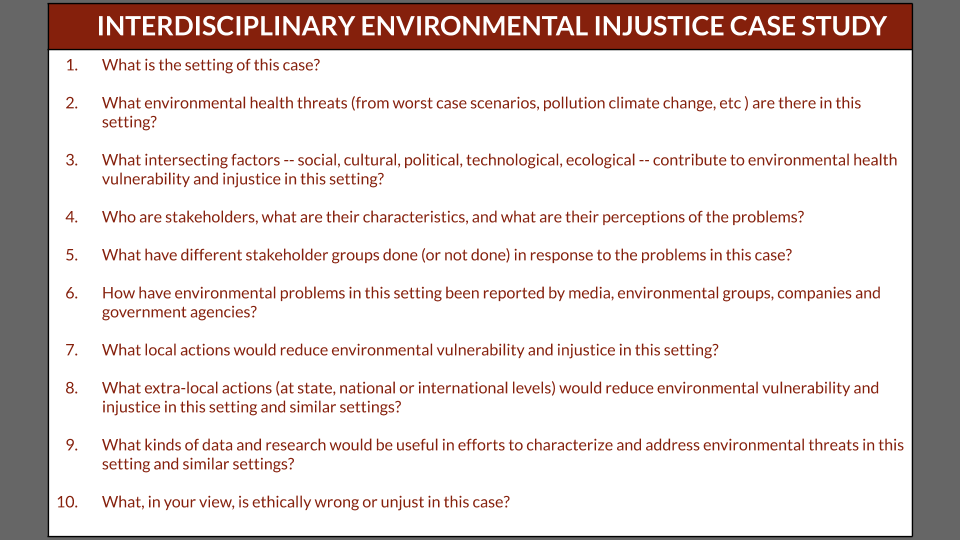

This is our purpose of the tour: to tell the story of Louisiana’s River Parishes in a way that sets the stage for change. The project design has many moving parts and players to help with this. The project is designed to connect university researchers -- including student researchers -- to communities struggling to address environmental injustice. Research on the Cancer Alley case was done by researchers at the University of California Irvine, in partnership with environmental activists and cultural leaders in Louisiana’s River Parishes -- using a case study framework that allows us to compare and connect the Louisiana case to other cases of environmental injustice around the world. Our environmental injustice case study framework is also used by UCI student researchers studying environmental injustice in California communities, for example, and by student researchers at University of Mexico Tech. At UCI, we focused on explosive, slow pollution and climate change disaster in California communities. At University of Mexico Tech, student research focuses on radiation hazards, primarily from uranium mining. The environmental injustice case study framework thus also allows us to connect many different types of environmental hazards, supporting concerted action to address them. Perhaps most important is the way a shared case study framework allows us to connect people in different places, with different experiences and skills, who can work together to deepen understanding of why environmental injustice happens and what a “just translation” will entail. “Just transition” is the name given to a still not-yet-figured-out future in which all people will have access to clean and healthy jobs, homes and environments, and the education needed to build these.

Our tour today doesn’t yet lead to a just transition. There is much work to do ahead. But we can get started, listening and learning from people in Cancer Alley."

"In this tour, many of you will be introduced to Southern Louisiana for the first time. It is a beautiful landscape, though now heavily polluted. It is also v†ery culturally rich. You'll get a glimpse of this on our tour through a stop at the Fee-Fo-Lay Cafe. It is also -- like many communities facing environmental injustice -- a very complicated place -- politically, economically and socially, because of the heavy presence of industry, beasu long-running, compound vulnerability are now exacerbated by the extreme weather associated with climate change. Because of COVID-19. There is a lot going on. Many different kinds of data, analysis and knowledge are needed to make sense of it all. This is why we’ll also introduce you to our EiJ case study framework and digital archiving project."

"The case study framework has ten questions, which together guide both characterization of places facing environmental injustice and identification of actions that would improve conditions in these places. These case studies are always a work in progress -- partly because of new hazards, but also because of the never-ending need to draw in more history, more textured understanding of stakeholders in the mix today, and more possibilities for protective action and inclusive prosperity going forward.

The case study framework is designed to see all these aspects of environmental injustice together. It is also designed to allow us to work together, thus working more quickly and drawing in different experiences and forms of expertise. UCI students, working in groups, produce quite extensive case studies in a week or two. We’re also running workshops with community activists to help them draw their different experiences and insights together, interlaced with knowledge of university researchers like us.'

"Lastly, the case study framework provides a structure -- what we call an architecture for preserving our research and knowledge over time so that others can use and build on it giong forward. As I know the community activists with us now are aware, there are many dimensions of environmental injustice that call for analysis and action, and floods of related documentation. It is hard to keep up with. The digital archive we are building provides a place for this documentation, and ways to focus both on particular places -- like Southern Louisiana -- and also on cross-cutting themes -- so that we can compare sites and work together on shared problems. Think of it as a house with different doorways, allowing for us to see environmental injustice from different angles.

The tour we’ll take you on now enters through one among many doorways into the material -- moving through a number of stops that will help you understand Louisiana’s River Parishes as a site of both environmental injustice and resistance. We’ll only be able to show you a little of the material at each site: you can return for further exploration later. You can also suggest material for us to add to the collection for a particular site. Our archive needs to continue to grow.

After the tour we’ll invite you to enter through a different doorway, moving through our case study questions. You can do this just after our tour, or later, on your own time or in a class or workshop we can help set up.

There are also other doorways into the material -- moving through it to produce creative writing or picture books for kids, for example, or to produce Instagram stories. Let us know what you think is important and what talents you have to share.

Let’s go now, though to the tour that follows the lead of organizations like the Whitney Plantation Museum and LEAN."

Tim Schütz, Kim Fortun and Prerna Srigyan. 7 October 2020, "Cancer Alley, Louisiana", Disaster STS Network, Platform for Experimental Collaborative Ethnography, last modified 14 February 2023, accessed 30 November 2024. http://465538.bc062.asia/content/cancer-alley-louisiana